From Proofs to Programs: The Deep Mathematical Roots of .NET LINQ 🤓

Some mathematical proofs we can write in LINQ

Have you ever stopped to consider what truly underpins the elegant, expressive power of .NET LINQ (Language Integrated Query)? It turns out that this cornerstone of modern C# and VB.NET development owes a massive debt to high-level mathematics, specifically concepts from functional programming and category theory.

It’s not just a convenient syntax—it’s a philosophical bridge between mathematical thought and computer program structure.

The Curry-Howard Correspondence: Programs as Proofs

The most fundamental concept linking computer science and mathematics is the Curry-Howard correspondence. This profound insight establishes a direct, structural relationship:

Types in a program correspond to propositions in logic.

A correct program (or function) corresponds to a proof of that proposition.

In this view, writing a program isn’t just giving instructions; it’s constructing a verifiable, logical proof that a certain type (a certain proposition) can be produced from another. This leads directly to fields like design and program verification, where tools can formally check if a program is logically sound, and even theorem proving, where programs are used to prove complex mathematical theorems.

Going from imperative programming (telling the computer how to do something) to functional programming (telling it what to calculate) is a step along this continuum. Further along lies languages like Idris, which are dependently typed—their type system is so rich it allows for proofs directly within the code.

The Genesis of LINQ: Declarative Power from Haskell

The core appeal of LINQ lies in its declarative programming style. Instead of painstakingly writing loops and conditions (the how), you state what you want:

// Imperative approach (The “How”)

var juneEmployees = new List<Employee>();

foreach (var emp in employees)

{

if (emp.MonthStarted == “June”)

{

juneEmployees.Add(emp);

}

}

// Declarative LINQ approach (The “What”)

var juneEmployees = from emp in employees

where emp.MonthStarted == “June”

select emp;

This idea isn’t new, but the beautiful way it’s implemented in LINQ was heavily inspired by the functional language Haskell. The C# language design was directly influenced by Haskell experts, particularly Erik Meijer.

Monads and LINQ’s Structure

The key conceptual borrowing is the monad, a concept from category theory.

In Haskell, monads are used to handle operations that involve sequencing computations, like I/O or state management. They provide a predictable, controlled structure for combining complex operations.

In LINQ, the familiar

SelectManymethod is, in essence, a slightly modified version of the Bind operation—the fundamental operation of a monad. The LINQ syntax is specifically designed to make operations on the sequence monad (which deals with collections likeIEnumerable<T>) feel intuitive and natural.

This is why, if you look at the principles, LINQ is absolutely considered functional programming. It treats functions as first-class objects (e.g., passing lambda expressions), emphasizes calculation over side effects, and encourages an immutable, data-centric approach.

Category Theory: The Abstract Backbone

Category theory is the mathematical engine behind concepts like the monad. It’s a general theory of mathematical structures and the relationships between them.

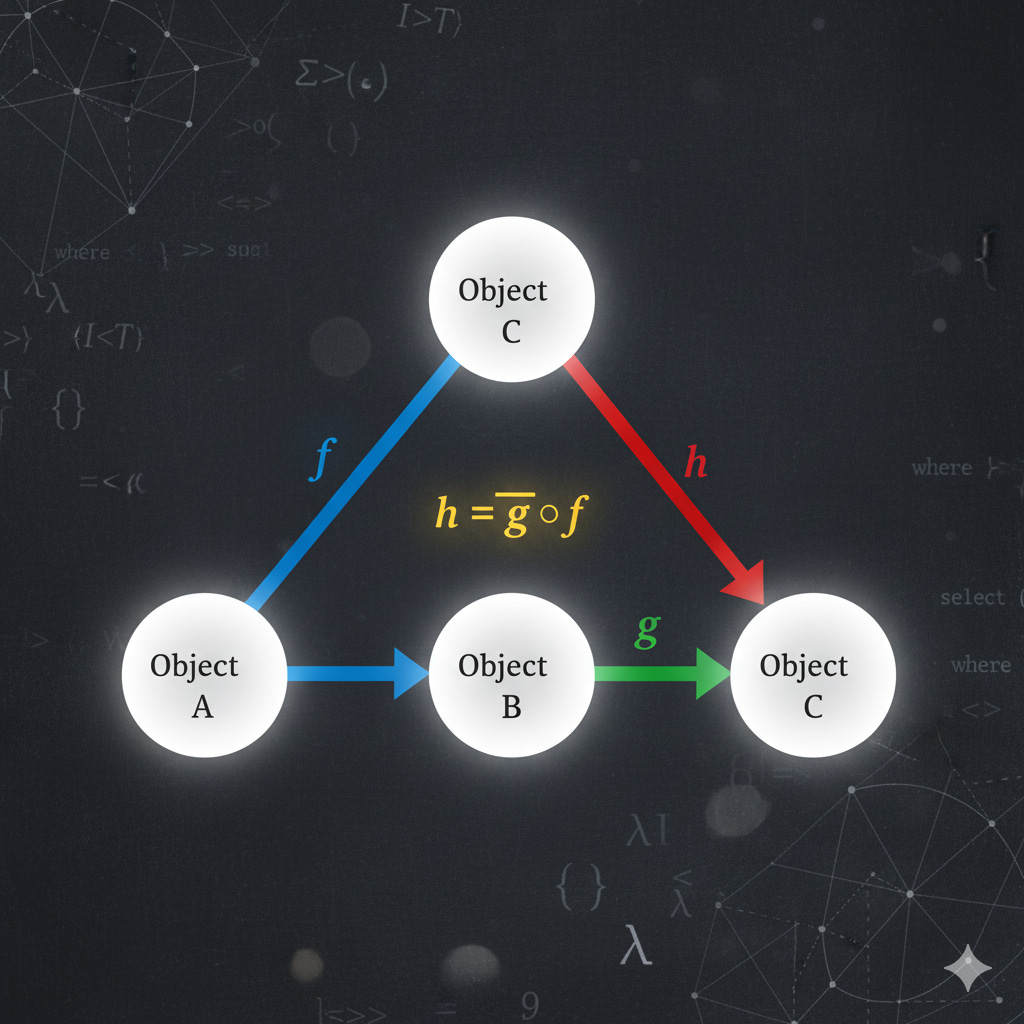

A Category consists of:

Objects: The things being related (e.g., types, sets, or mathematical structures).

Morphisms (Arrows): The relationships or structure-preserving maps between objects (e.g., functions or transformations).

Crucially, these morphisms must adhere to rules like associativity (composing relationships) and having an identity (a relationship of an object to itself).

Why Category Theory Matters to Your Code

This abstract mathematics matters when you write and test your code because these rules—associativity, identity, and composition—are essential properties of good, predictable software.

When a LINQ query works correctly, it is because the underlying design guarantees that the operations (the morphisms/functions) can be composed and reasoned about reliably, just like mathematical functions. This is why practices like Test-Driven Development (TDD) are so valuable: by writing the test first, you are essentially defining the proposition (what the code should do) and then writing the code to provide the proof (the correct implementation).

In short, when you write an elegant LINQ query, you’re not just writing C#; you are standing on the shoulders of giants in logic and abstract algebra, proving a tiny, executable theorem.